Earlier this month, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese visited Kyiv to meet with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, during which he pledged further monetary assistance to Ukraine. The new assistance package consists of:

$99.5 million AUD in military assistance, bringing Australia’s total military assistance to Ukraine to approximately $388 million AUD,

And a further $8.7 million AUD to Ukraine’s Border Guard Service, which deals with border management and cyber security.

Australia’s newest contributions make it the largest non-NATO contributor to Ukraine.

The Lowy Institute found in a 2022 poll that 34% of Australians said they would decrease foreign aid spending if they were formulating the federal budget. A further 42% said they would keep foreign aid spending about the same.

Accompanying these views is often a misconception of how much Australia truly spends on foreign aid. In 2018, it was found that, on average, Australians believed that we spent over 15 times more than the country actually did at that time on foreign aid.

In the 2021-2022 budget, the former coalition government allocated $4.335 billion AUD for foreign aid. This figure decreased by $144 million from the previous 2020-21 budget.

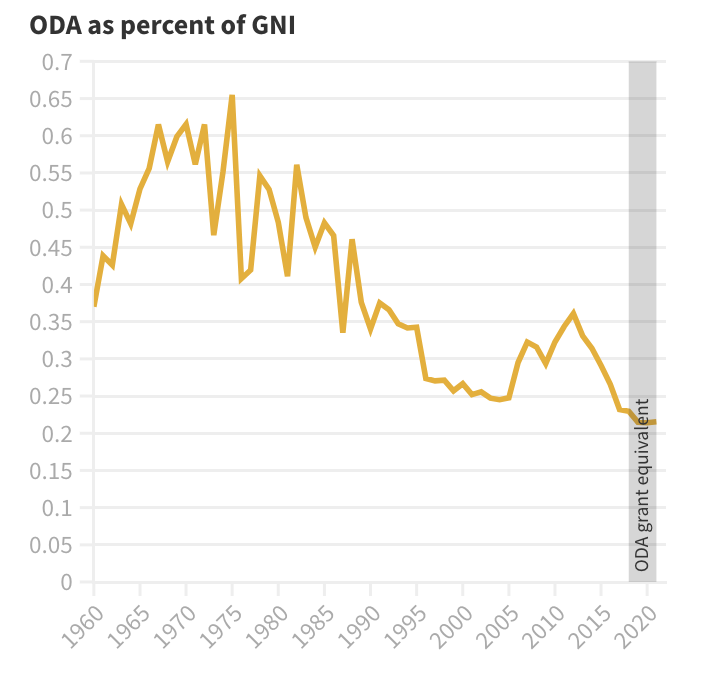

This means that in 2021, Australia only spent 0.22% of its Gross National Income (GNI) on Official Development Assistance (ODA). Australia’s ODA has been on a downwards trend for many years now, making it one of the least generous countries internationally.

Source: OECD

For decades now, 0.7% ODA of a country’s GNI is the recognised target for foreign aid spending. The United Kingdom (UK) met this in 2013 and maintained it until 2020. In 2021, the UK’s ODA was 0.5% of its GNI.

Therefore, when put into proportion, Australia’s foreign aid spending is not incredibly high but small in comparison to its international partners.

So where does our foreign aid spending go?

In 2019-2020, 58.3% of Australian ODA went to Asia and Oceania (not including South and Central Asia).

The biggest recipients of our aid were Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, Solomon Islands, Bangladesh, Timor-Leste, Myanmar, Afghanistan, Philippines, Vanuatu, and Viet Nam.

How is it being spent?

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) often publishes how its ODA is being spent in the various recipient countries. Most Australian foreign aid is now targeted at the management of COVID-19 in developing countries with already fragile health systems.

Health security, stability and economic recovery are the three essential pillars Australia’s foreign aid seeks to assist.

What this means in practical terms can be explained through the example of Papua New Guinea. The aid provided to Papua New Guinea in the 2021-2022 budget is targeted for:

Supporting essential services,

Improving sexual and reproductive health and rights services,

Defence building,

Strengthening protection for victims of crime,

Education,

And food security.

Is it worth it?

The issues that foreign aid spending seeks to address are ones of disproportionate inequality. If Australia wants to be a leader in political, social and economic equity, it must continue to monetarily assist developing countries.

Given the almost decade-long decline foreign aid spending has been in, it is no secret that is it viewed as something that can be decreased consistently. The issue stems from the fact that foreign policy is not an electoral concern for most. Since there are no real electoral implications if politicians cut back on foreign aid spending, they have been doing so.

Considering Australians' inflated perception of how much money we give to foreign countries, it is likely that cuts to foreign aid are well received domestically. But in the international scene, a lack of generosity sees the loss of credibility points.

It is worth mentioning that the lack of knowledge about how much money is truly being spent relative to our economy also worsens people’s mistrust and lack of support for foreign aid spending.

But it is something Australia must do for the right reasons. Many have argued that if anything, foreign aid spending improves Australia’s economic potential by financing new industries and capacities abroad.

Whilst this is true, it should not be the only lens through which we justify assisting countries and their pursuit of sustainable development. Foreign aid spending is at the heart of building a more just, compassionate, and cosmopolitan international community.

Wealthier countries hold a unique responsibility to their developing partners, particularly since these countries, like Australia, developed at the expense of their peers.

When it comes to ODA spending, Australia must move away from a transactional foreign policy framework to a meaningful and fair one. We should be pulling our weight.

Hopefully, the Labor government’s new budget, expected to be revealed in October, addresses this need.

Before you move on to our next piece of wonderful content, we would love to grab your feedback via the form here - Edge of the Crowd reader survey.