Last week, To Pimp a Butterfly became the highest-ranked album on the community ranking website Rate Your Music, overtaking Radiohead's OK Computer.

I used to think hip-hop was meant to be comedic. My introduction to the genre was through Eminem's 2010 album Recovery, which didn't totally hook me, but made me curious enough to dig into his catalogue. My favourite tracks at the time quickly became the upbeat and jokey tracks "Without Me", "My Name Is" and "The Real Slim Shady".

In the years that followed, I found my love for hip-hop a little closer to home, listening to artists like the Hilltop Hoods, Seth Sentry, and Koolism. These guys were putting out tracks that were still upbeat enough to keep me bobbing my head to the beat but had more relevant cultural references that made their punchlines even funnier.

A lot of references to hip-hop culture from these albums were going over my head, so eventually, I decided to listen to some American hip-hop. I bought a couple of Kanye albums and got pretty hooked on the earlier ones like College Dropout and Graduation, where he had heaps of crack-up lines. For a while, those laugh-out-loud lines were what kept me coming back.

It took me many more listens to recognise the political messages loaded within his tracks. Both indirectly and explicitly, he was rapping about life as a black person in the USA.

It challenged what I thought rap could do. I thought it was a vehicle for comedy, or to tell stories, but I didn't realise its power as a protest genre. It let people talk – just straight-up talk, not sing, or scream – about what they needed to, what was important to them, and what they were going through.

Honestly, it totally went over my head that hip-hop had its roots firmly in notions of protest from its very first emergence out of New York City in the 70s.

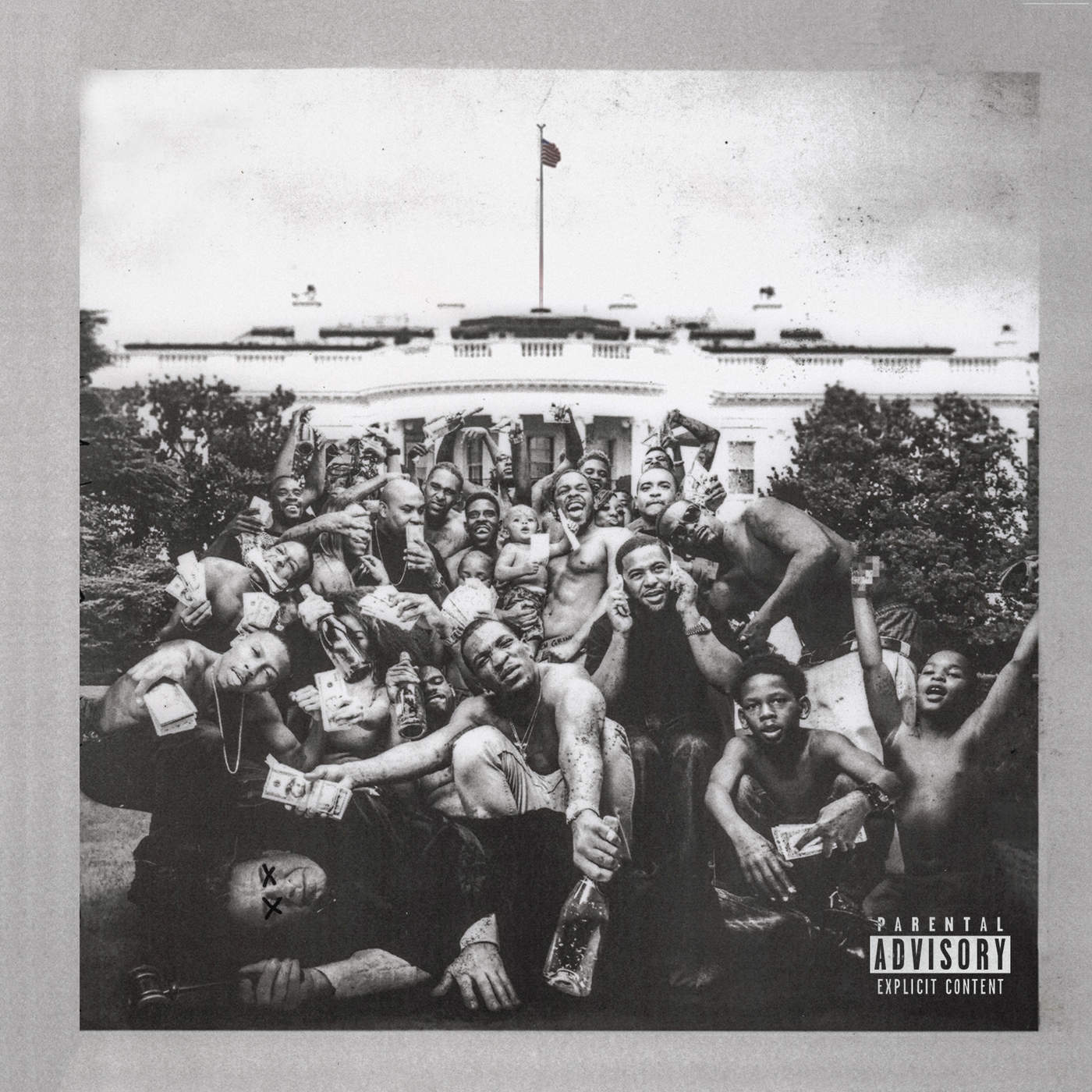

I don't remember why I bought To Pimp A Butterfly in 2015. I remember the CD cover looked amazing and maybe I'd seen some posts about it somewhere online. I'd never listened to Kendrick Lamar before, but I don't think having any prior knowledge would have prepared me for what I was about to experience.

I felt absolutely baffled by the album. Lyrically, it seemed to have more consciousness and complexity than I'd heard before, but from the very first track, it also had such a groove that you felt like bouncing the whole way through.

In most of the hip-hop I'd listened to so far, albums often had one song that was dedicated to being 'political'. To emphasise its importance, it would sonically stand out from the rest of the record, exclusive in its seriousness to drive its point home.

Kendrick Lamar refused this division. He cleverly weaved the politics through the album, massaging them into the grooves of the record. This could be felt in the instrumentation itself, where the funk and jazz function as reference and homage to the deep history of black music.

From the overwhelming funk sound of the first track, "Wesley's Theory", I was wondering what it meant for this hip-hop to be so far departed from what I thought hip-hop was meant to sound like.

This confusion was cemented by the second track "For Free? – Interlude".

Saxophones? Jazz? A woman starts dissing the hell out of someone while a jazz band goes to town and then Kendrick comes out with a verse that seems rhythmically uncountable, sounding free but at the same time perfectly in step with the instrumental.

Every track on this album evoked a similar surprise. It took me so many listens to comprehend the instrumentals before I could even properly dive into Kendrick's lyrical content.

I remember one specific listen where this all came together for me in the final track of the album "Mortal Man". It's a mammoth 12-minute track that sees Kendrick ask questions of himself, his fans, his community, and eventually the ghost of 2Pac.

It also features a frequent reference to Nelson Mandela. Later I would find out that these references drive the core of the album, as Kendrick rewrote large chunks of the album after a visit to South Africa and learning about the revolutionary icon.

The chorus gives me chills every time I hear it. It let me know that Kendrick was a poet unlike any I'd heard before.

"The ghost of Mandela, hope my flows stay propellin'

Let these words be your Earth and moon, you consume every message

As I lead this army, make room for mistakes and depression

And with that being said, my nigga, let me ask this question:"

It struck home for me. My father is an Indian who grew up in South Africa during apartheid in the 40s and 50s. He grew up admiring men like Nelson Mandela, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King that fought against racism and for the rights of underprivileged people and I was raised hearing stories about them and their struggles.

I don't have the same lived experience as Kendrick Lamar, the experience of being a black man in the USA. When you have this distance, it can be hard to connect with music on some levels without a path in. These references to Nelson Mandela and South Africa were mine.

I knew the power of the voice of Mandela, as I saw the ripples of it in my father's person. I didn't know this same strength could be present in hip-hop or even music until I listened to Kendrick Lamar, and his verses rippled through me.

I started to understand the power of Kendrick renaming himself as King Kunta, or recontextualising the N-word with "Negus", meaning Ethiopian royalty.

But I also began to understand the power of the subtler, more personal statements within the album. As black feminist writers like Kimberlé Crenshaw and Audre Lorde said, "the personal is political".

In tracks like "u", Kendrick lets the listener into a fractured hotel room where he had a severe breakdown.

The song features a chorus where he states "Loving you is complicated", a statement directed to himself. Later in the track, he raps two verses with a hauntingly shattered voice, reflecting on the mistakes he's made and the self-hatred that resulted from it.

The album puts these personal explorations in context through its analysis of institutional oppression, the legacy of slavery and the trauma inflicted on black people in America. When understood together, we see that both the personal and the larger systemic explorations of To Pimp a Butterfly converge to be about the same thing.

Kendrick Lamar's catalogue has shown him to be one of the most innovative and evocative artists of our time. His two albums since To Pimp a Butterfly, DAMN., and Mr Morale and the Big Steppers have been decidedly diverse in both sound and content, but the uniqueness of this album will render it a touchstone of this generation of both hip-hop music and music more widely.

To Pimp a Butterfly's recent rise to the top of the community-ranked album charts on Rate Your Music proves its ongoing relevance and the power of Kendrick's message. It's an album that will always offer more every time you listen to it. Its sonic and lyrical depth deserves the effort and time you need to unpack its profound content and it never sounds the same twice.

Before you move on, why not give our Facebook page a like here. Or give our Twitter account a follow to keep up with our work here.